Five years ago, more than half a million adults in Philadelphia lacked basic literacy and work skills, imperiling their ability to land jobs and climb out of poverty, the Philadelphia Workforce Investment Board reported. Yet at the same time, hundreds of literacy providers operated scattershot programs all over the city, albeit with few resources, fewer notable metrics, and even less oversight.

The city was suffering a “serious literacy crisis,” Mayor Michael A. Nutter said, and he vowed to fix it, beginning in his own office. He retooled The Mayor’s Commission on Literacy, funded it with $1 million, and hired a new director. Then the bottom fell out: the state pulled its annual $4 million in literacy funding to the City of Brotherly Love, forcing the commission to take a new look at how to address the problem.

The solution, they decided, was digital.

In the city at that time, low-literate adult learners were forced to embark on a “wild-goose chase” for services, the former director discovered. For students with fourth- to sixth-grade literacy levels in particular, demand far exceeded supply. Some things were working, though. So commissioners gathered the best practices and built a collaborative. They created a central registration and enrollment system to both track and attract students, and trained all literacy volunteers — from three ladies tutoring in a church basement to hundreds of facilitators — so they could lead cohort-based programs online. When they couldn’t find digital courses to serve low-literate adults, they paid contractors to create them.

Today, Philadelphia sponsors what organizers say is the first free online interactive adult-education program in the nation. At 30 literacy organizations and three campuses called myPLACE (Philadelphia Literacy and Adult Career Education), students learn together in groups (or cohorts), attend class in-person and online, and work with a learning coach who sends them texts, e-mails, even postcards to keep them engaged and moving forward. The goal is to help them earn a GED, read at a community-college level, and ultimately land a job. In just over a year, more than 3,000 adults have either completed basic literacy classes online, earned their GEDs, or have been launched on a career path. The U.S. Department of Education’s Digital Promise initiative has named myPLACE a model site. The organizers’ goal this year: to reach 16,000 adults online, on their phones, in person, or at home.

Philadelphia Mayor Michael A. Nutter (third from the right) at a ribbon-cutting ceremony celebrating the opening of three myPLACE campuses in 2014. (Source: The Mayor’s Commission on Literacy)

Yashi Maynard is one of the program’s early success stories. During the week, the 26-year-old works as a van attendant for autistic children, and she spends Saturdays in classes alongside other behavioral health workers. Maynard hopes to become a certified recovery specialist. Three years ago, though, she was at a crossroads — with limited options.

“My probation officer said, ‘Either you get locked up or you go into a program,’” recalls Maynard, who’d been to jail before and selected the drug rehab option only to avoid a return trip behind bars. While in rehab, though, she connected with Narcotics Anonymous, got clean, and begged to be transferred to a halfway house rather than return to the streets. After nine months at the halfway house, she was sent on her way, she says, without any resources or housing. The staff did mention one thing: “They let me know about 1199C and the GED.”

The District 1199C Training and Upgrading Fund is a health care-union initiative serving 50 hospitals in the Delaware Valley. In an office building a couple of blocks from City Hall, the district runs free training and literacy programs at its myPLACE hub. Maynard called the center, followed-up with a literacy assessment test online, and met with a learning coach. When she showed up for her first class, Maynard brought just one thing with her: the swagger that had gotten her into trouble innumerable times in high school, which she dropped out of as a pregnant 14-year-old.

“I went in there rebellious, with no book bag, no pen. I remember Miss Theresa Bird, she’s one of the instructors there. I said to her ‘I’m here.’ She said, ‘No, you’re not here. Nobody else came in here unprepared.’ She sent me home. Then I came back with paper and pen and sat in the back because I was struggling. She would give us homework. We could go online and take practice tests there in the computer room. I was there everyday of the week until I got it.” Working at her own pace, and with a free tutor available online and in person, Maynard got herself up to speed on basic reading, math, comprehension and computer skills, and earned her GED. Since she was able to function at the fourth-grade level or above, she started with the online class, “Introduction to Adult Learning,” and moved forward, working independently on Canvas, a Blackboard-like learning management system that’s available at myPLACE campuses as well as via a mobile app. Videos support much of the content. Then she got her driver’s license, learned about interviewing, and finally landed a job.

Maynard is among the more than 200,000 people with criminal records who live in Philadelphia, many of whom test at zero to third grade reading, writing and math levels.

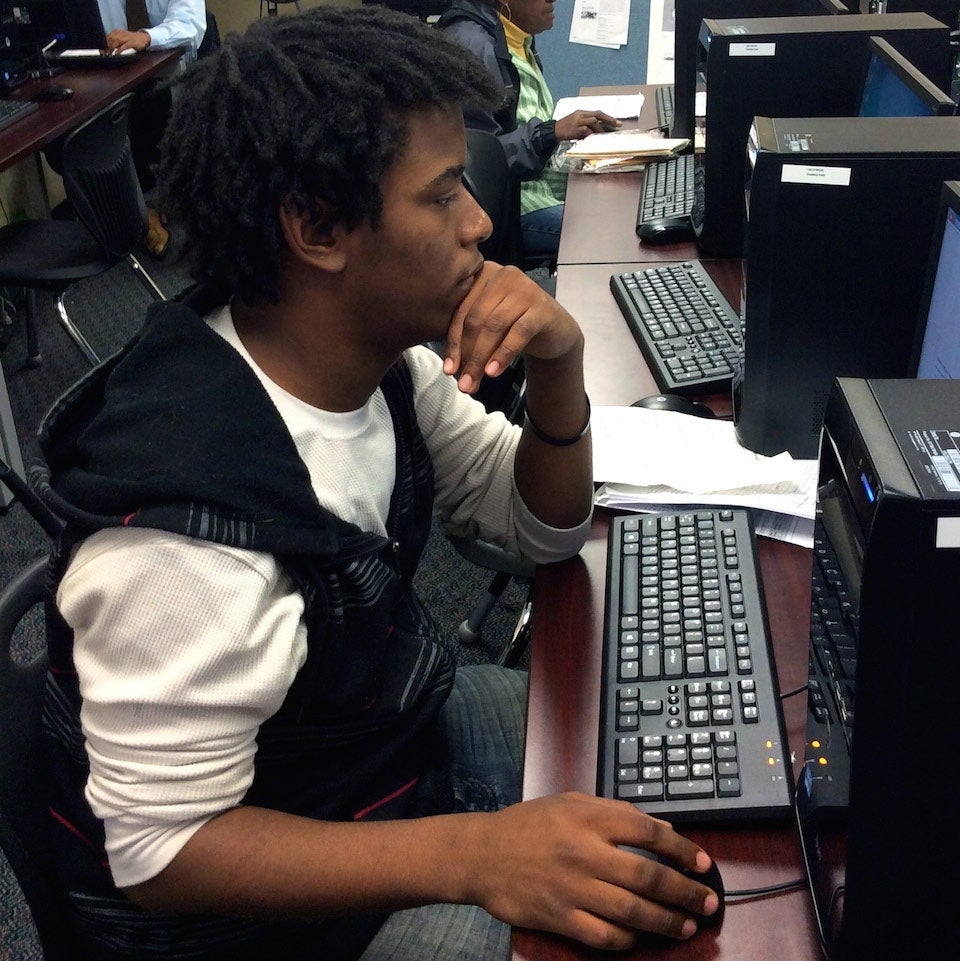

Philadelphia resident David Johnson, 22, at the District 1199C myPLACE hub. (Photo credit: Carol Leonetti Dannhauser)

“The whole purpose of myPLACE was to create a system with a full menu of services,” says Diane Inverso, the commission’s interim executive director. Today, there’s a pipeline that takes learners from the first phone call all the way through to online courses and job placement.

One recent Tuesday at 1199C, eight students worked independently in the center’s computer lab. Stephanie Webb, the site administrator and a learning coach there, moved from student to student, helping them navigate the career path questionnaire, or negotiate their GED prep classes, or make their way through goals and inventories. In the classroom next door, a volunteer tutor worked on phonics with three students, all of whom test at the zero to 2.5 grade level.

One student, 22-year-old David Johnson, graduated from the now-shuttered Germantown High School, but says, “there wasn’t really much teaching going on there. It was a very bad school and they shut it down.” He took the test for community college repeatedly, but couldn’t get in. After graduation, Johnson worked under-the-table cleaning planes at the airport, but lost his job. His mother sent him to myPLACE for help. “I like how all the assignments are done on the computer. I’m not a big fan of writing,” says Johnson, who has no computer or Internet access at home. “I usually stay here until the building closes and they kick me out. My goal is to get a better job.”

Johnson, like others at myPLACE, will progress at his own pace, with a learning coach to help him along the way — whether virtually or in person. All along, digital pre-tests and post-tests will measure his progress, says Jennifer Kobrin, associate director of the Mayor’s Commission on Literacy.

Her colleague Inverso says, “We took a gamble on this. We thought they would come — and they sure as heck have. We wanted to give people an opportunity to not go on a waiting list but to participate in something where their digital skills are developed. My biggest desire was to establish the system, then go back and qualify it later.” Adds Kobrin, “We know it’s working. We now have data to back it up.”

Philadelphia’s myPLACE program has helped thousands of low-literate adults gain the skills they need to improve their lives, but there is much more work to be done. More than 36 million adults in the United States alone lack basic literacy skills. That’s why XPRIZE, in partnership with the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy and Dollar General Literacy Foundation, launched the $7M Adult Literacy XPRIZE, a global competition challenging teams to develop mobile applications for adult learners that result in the greatest increase in literacy skills in just 12 months.

Join us in this fight against illiteracy. Visit http://adultliteracy.xprize.org/ to learn more about the competition and to register to compete.

Carol Leonetti Dannhauser is an award-winning journalist whose work appears in print, online and on television.